While we may not realize it, much of our decision-making process is based on comparison. It’s a central tenant of how we determine the value of all things, especially products and services. The decoy effect is a cognitive bias that plays on this idea of comparison. More specifically, it explores how we compare specific dimensions to make decisions.

Examples of such dimensions include but are not limited to price, size, speed, aesthetic, novelty, etc. While using comparison as a way to determine value is nothing new, the decoy effect takes it a step further.

We can look to the most relatable example of the decoy effect to illustrate this: popcorn pricing at the movie theater. The question is, why do we always end up buying a large bucket of popcorn? Let’s break it down. In the case of popcorn, there are two dimensions we are comparing: size and price.

Small, medium, and large make sense, but when we use those to assess the prices, the obvious choice is to go with large. Let’s go through this thought process:

- The small is $4 and compared to the medium at $6.50 that makes sense. More popcorn equals a higher price.

- The medium is $6.50 but compared to the large at $7.00 this no longer sounds like a deal. You’re going to get much more popcorn for just 50 cents. This instantly eliminates the medium as an option.

- Now the choices are the small vs the large, but since it’s hard to make an obvious comparison here, we opt for the one that we can rationalize, choosing the large.

This is the decoy effect in action.

What Is The Decoy Effect

According to Wikipedia:

“The decoy effect is the phenomenon whereby consumers will tend to have a specific change in preference between two options when also presented with a third option that is asymmetrically dominated.”

Let me deconstruct this in simpler terms. First, asymmetrically dominated means that when you compare options, there is clearly one that is worse than another in every way – it is dominated by another option.

So then the decoy effect is where a decoy option (which is asymmetrically dominated) is introduced as a choice, and that option influences the popularity of one of the other two options. This same idea can be visualized when looking at these options on a simple graph against two dimensions.

There are three options here: the target, the competition, and the decoy. As you can see there are clear differences on both dimensions between the target (what the business wants you to pick) and the competition (the less desirable option). The designated area below the curve is where the decoy should be placed. There are a few key points about how it is positioned.

1). It is often placed closer to the target, so that the comparison between the two is more easily accomplished and it is clear it is asymmetrically dominated.

2). It can be worse on one or both dimensions, but the more change it holds versus the target, the more difficult comparison becomes.

When there are only two options, most people tend to choose based on their preferences, but when there are three, people rely more on comparison. Let’s return to the example of popcorn pricing.

In this framework, dimension 1 would be price and dimension 2 would be size. Then if we assign a letter grade to the options, A is the large popcorn for $7 (target) and B is the small popcorn for $4 (competition).

Most people would be split on this choice, as some would want more popcorn, while others would want the cheaper price. What changes this behavior is the introduction of the decoy as A-, which is the medium popcorn at $6.50. This gets defined as A- because it is dominated by option A on both dimensions: just as expensive, but for less popcorn.

This changes things dramatically. It is much easier to make a comparison between A and A-, and as such, more people end up picking option A. While it may not seem rational, this outcome has been proven repeatedly.

One of the most famous experiments was conducted by Dan Ariely, Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics at Duke University, when he applied these principles to purchasing subscriptions for the Economist.

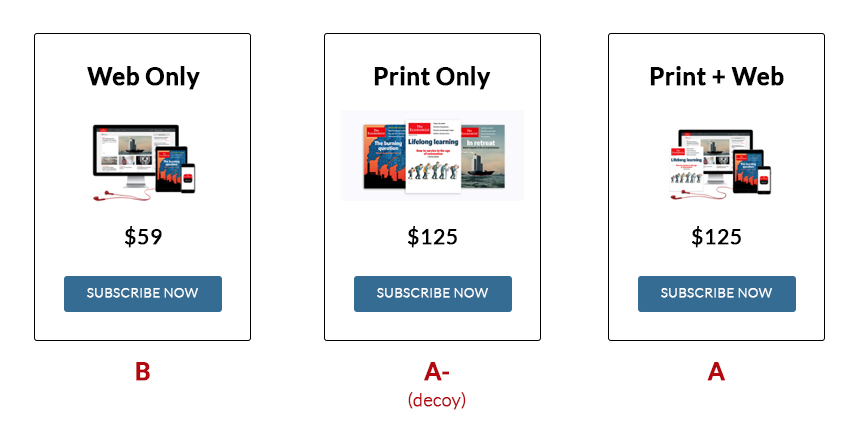

In a study using 100 MIT students, Ariely asked them to pick an Economist subscription from three options: Web Only for $59, Print Only for $125, and Print + Web for $125. Of the 100 students, 84 chose Print + Web, 16 chose Web only, and no one picked Print only.

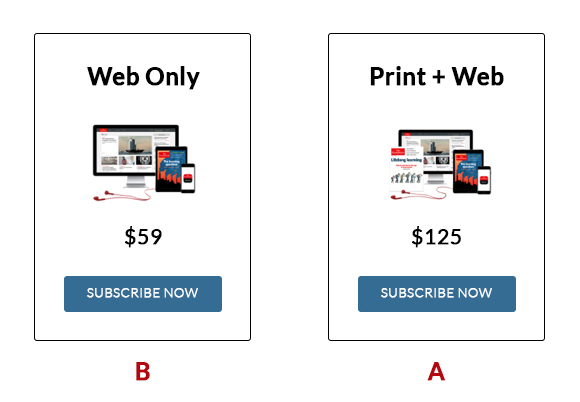

If we categorized each option based on our theoretical framework above, Print + Web is the target (A), Web only is the competition (B), and Print only is the decoy (A-)… and an effective one at that. When Ariely wanted to know why bother with the decoy if no one picked it, he tried the study again.

This time he asked another 100 students to pick between the Print + Web and Web Only options. The results shifted dramatically, as 32 chose Print + Web, while 68 chose Web only.

In this case, the target option of Print + Web went from 86% down to 32% because of the missing decoy option. This illustrates just how powerful the decoy effect can be.

The Decoy Effect in Action

Popcorn and the Economist aren’t the only ones using this approach to pricing in the real world. You can actually find it at play almost everywhere. Here are some recent examples I came across in the wild.

The first one is Google for their Pixel line of phones. This use case is very straightforward. The dimensions are the price and version of the phone.Pricing both the Pixel 4 and Pixel 3 at $799 makes it clear they want the Pixel 4 to serve as the target, while the Pixel 3 is the decoy (same price and older version).

Another example is seen on Adobe’s site for subscriptions to their Creative Suite software. In this case, the dimensions are the different programs available and the price point.

While it could be argued which is the target here, A or B, the decoy is clearly the Photoshop only option. It has fewer programs included, as well as a higher price point than the bundled version for Photography.

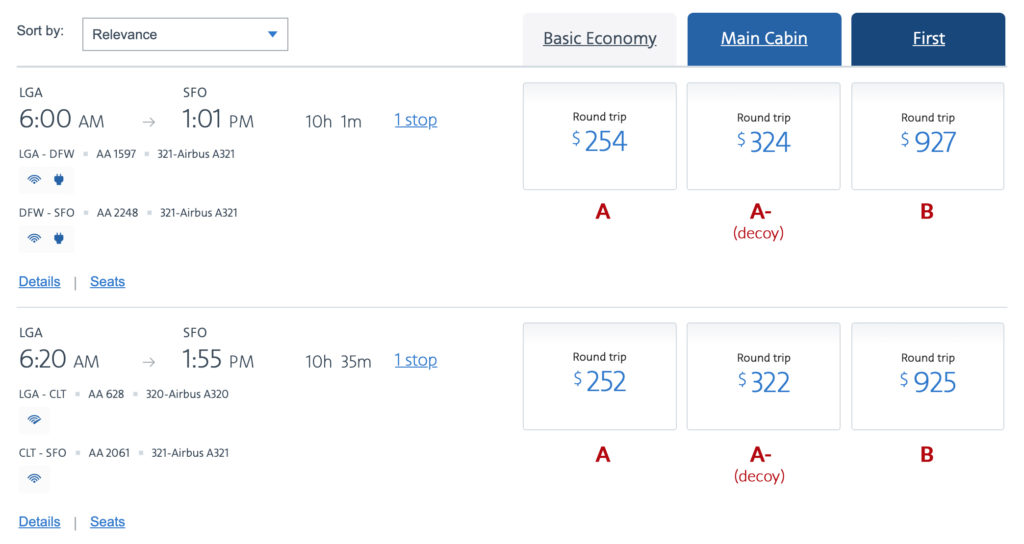

Airline pricing offers us another glimpse of this in action. This is the American Airlines flight pricing, where the two dimensions are the type of ticket and price.

Again, some consumers may be more price-sensitive than others, but most are happy to spend less for the minimal perks offered to go from Basic to Main, but this is where the primary comparison occurs.

As you can see, the decoy effect is in play across all industries and types of products and services.

Decoys for E-commerce

The decoy effect is everywhere, from airlines and tech companies to SaaS and retail – comparison is a powerful tool in everyone’s digital product toolkit. Here are just a few best practices on how to leverage it.

Start With Three Options

One of the tenants of the decoy effect is to have three options. While more is doable, this is the perfect starting point where you can clearly think through the target, competition, and decoy and how they live on their different dimensions.

Once this baseline is created, it becomes easier to build on but beware of making things overly complicated. The biggest value of sticking to three is that it makes it much easier to compare, which leads us to point number two.

Make Comparisons Clear

Some products and services are far more complicated than popcorn. The key is to not overwhelm your customer with things to compare. The easier you can make it to compare options across dimensions the better.

More often than not, one of these dimensions will be price, which is straightforward. The other one can get tricky, based on what you are selling. If there is a primary feature that you can highlight, that makes things simple, but if not, try to find ways to categorize features to make the point. These groupings will make it easier to compare on a single dimension versus multiple features.

Of course, picking category names can be tricky, as you don’t want to alienate your go-to option with a certain connotation. For example categorizing things as gold, silver, and bronze, will make people want to pick gold, but if that’s not your target, it’s not a great approach. Instead, try to come up with groupings that still highlight differences, but that are less polarizing (as we’ll see below in the AT&T example).

Leverage Bundling

When you don’t have different levels of single products or services, you can leverage bundling to make the value add and create decoys in a more artificial way.

This is exactly what the Economist did with their two products print and web. By creating a bundle of the two, they were able to execute the decoy effect to perfection, without making things more complex.

Use Pricing Tables

A common tenant for decoys is to present the information in pricing tables and for good reason. First, it gives you a structure to present the key dimensions you want to communicate. Second, it makes it very easy not only to compare, but also to highlight the preferred option you want your customers to select.

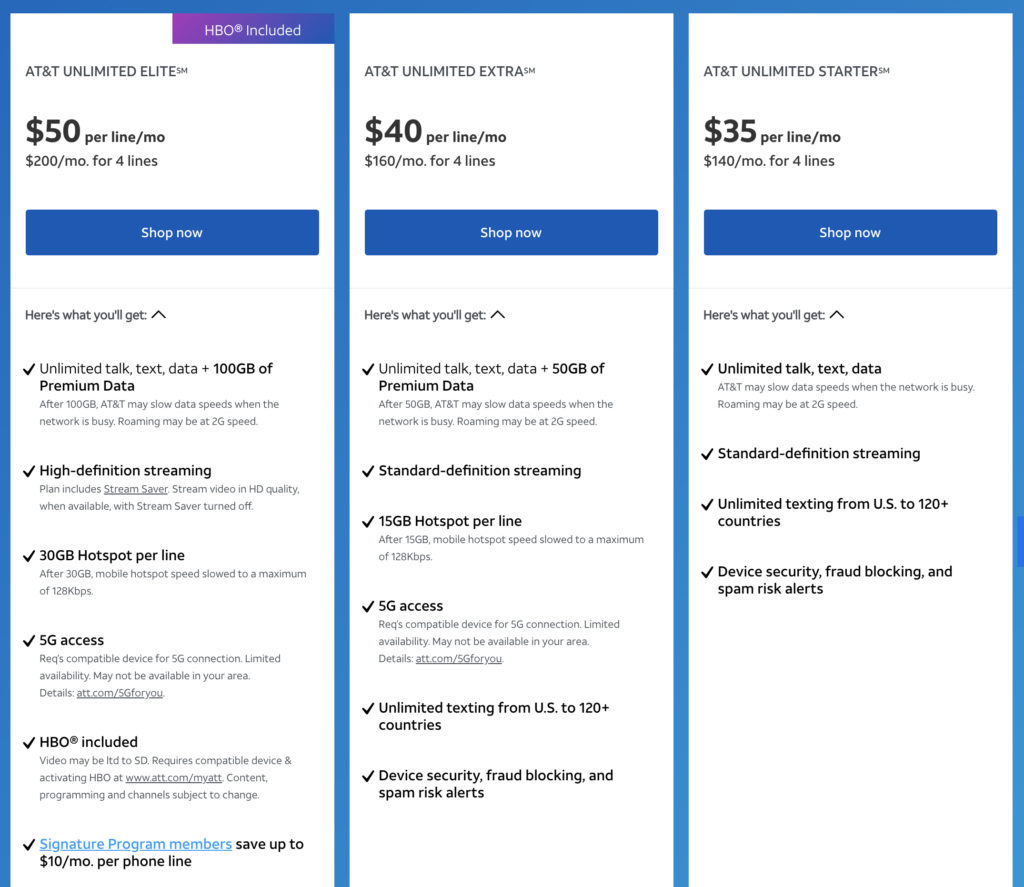

Here’s an example from AT&T’s website on plan pricing that hits on many of these key ideas:

- The options are laid out in a pricing table and they are able to draw your eye to the target: the unlimited plan with HBO included!

- There are only three options to navigate, the target, the competition, and the decoy, which keeps things easier to compare.

- While there are many features highlighted in each option, they are categorized by Elite, Extra, and Starter to make it easier to communicate the value add in a simpler way (they also don’t make any choice seem worse than the other).

People often don’t know what they want, so providing points for comparison, helps them make decisions. All of this allows the decoy effect to shine.

The Last Word

The decoy effect is a powerful tool in the world of e-commerce, especially when it comes to pricing strategy. Generally, pricing is hard to figure out, especially for start-ups, so using the principles of the decoy effect can be a great starting point for any product or service.

That being said, there are some important things to keep in mind when using the decoy effect.

One is that the dimensions where differences occur must be meaningful to the consumer. If they aren’t (i.e. they don’t care about that particular feature), then it has little sway on the decision-making process. Furthermore, if the decoy is not sufficiently undesirable (not dominated enough), then the impact of its presence will be greatly diminished.

Ultimately, the goal is to provide an illusion of a better bargain through comparison or what is more generally called relativity. It is how choice is impacted in the buying process and serves as a great tool for improving conversion and guiding users to the optimal outcome.

Sources

Adding Asymmetrically Dominated Alternatives by Joel Huber, John W. Puto, Christopher P. Puto

Dan Ariely – Pricing the Economist (Youtube)

Decoy Effect (Wikipedia)

Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely

Priceless by William Poundstone

related reading